Ancient Texts and the History of Medicine

What ancient written records can teach us about the past and future of medicine.

In December, I had the incredible opportunity to take a closer look at the hieroglyphic records featured in ancient Egyptian temples, such as inside the perfume and medicine room of the Temple of Horus in Edfu, which is situated on the bank of the Nile River.

I was amazed by the symbols indicating specific doses of different plant ingredients. The ancient Egyptians were clearly testing and formulating highly refined blends of various herbs and essential oils pressed from fresh flowers. Standing in the ‘perfume and medicine’ room brought all sorts of questions to mind. Where else in the world do we have records of ancient medicine? Have all of these been translated from their ancient languages? How much could we learn from these recipes by using the tools of modern science to evaluate these herbal products and their ingredients?

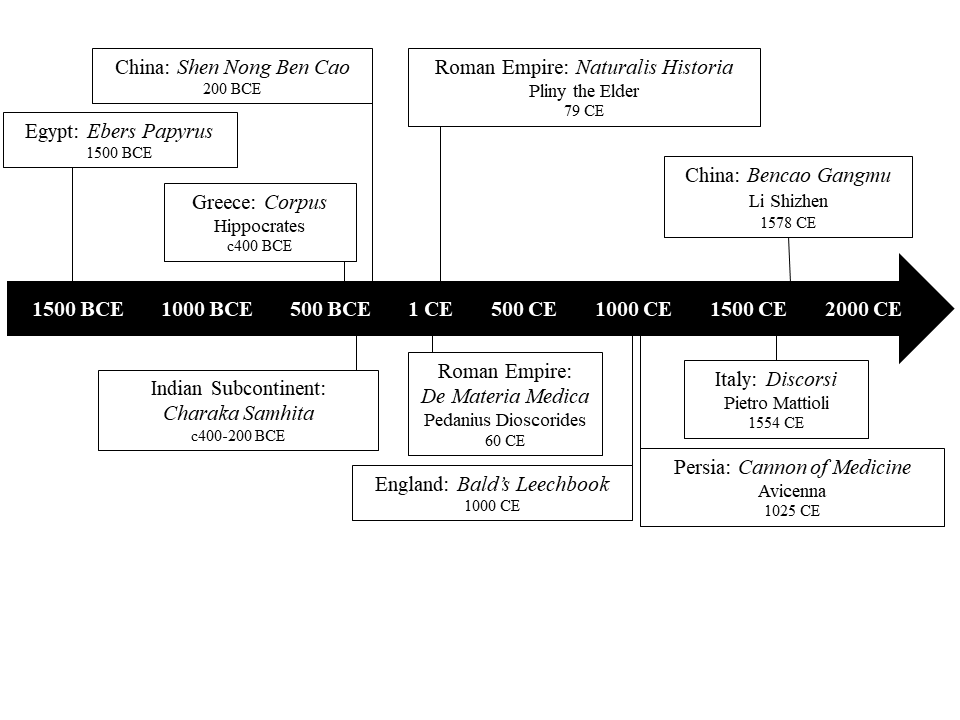

In today’s post, I’ll review some of the most notable ancient written records from 1500 BCE (before common era) up until ~200 CE (common era). We’ll cover more recent texts (from the middle ages onward) in a future post.

Records from Ancient Egypt

Some of the earliest written records of medicinal plant use, or materia medica currently preserved, date back to the times of Ancient Egypt. The Ebers Papyrus, named for Georg Ebers—who purchased the scroll in Thebes, Egypt in 1874—is one of the oldest and most important of the preserved medical documents discovered thus far.

The scroll, which has been dated to approximately 1550 BCE, is 20 meters long, and contains about 700 formulas and remedies using plant ingredients for various ailments.

Traditional Chinese Medicine

Another early written record linked to an ancient medical tradition is the Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing (Drug Treatise of the Divine Countryman), which was created in China around 200 BCE. The treatise contains an extensive list of 365 drugs, mostly of plant origin. Importantly, the text included detailed information about specific factors related to the plant ingredients (geographic origin, collection time, therapeutic properties, preparation, and dosing); modern scientific research has shown that these factors have a significant impact on plant chemistry and pharmacological activity.

The Hippocratic Corpus

One of the most well-known compilations of early medical works was the Hippocratic Corpus, a collection of 60 texts from circa 400 BCE that emerged from the Hippocratic school of thought, led by the teachings of Hippocrates of Kos. Hippocrates is best known as the Father of Western Medicine, and is credited with writing an Oath, known by most as the Hippocratic Oath, which is still repeated by students at the completion of their medical training—albeit in a modernized form.

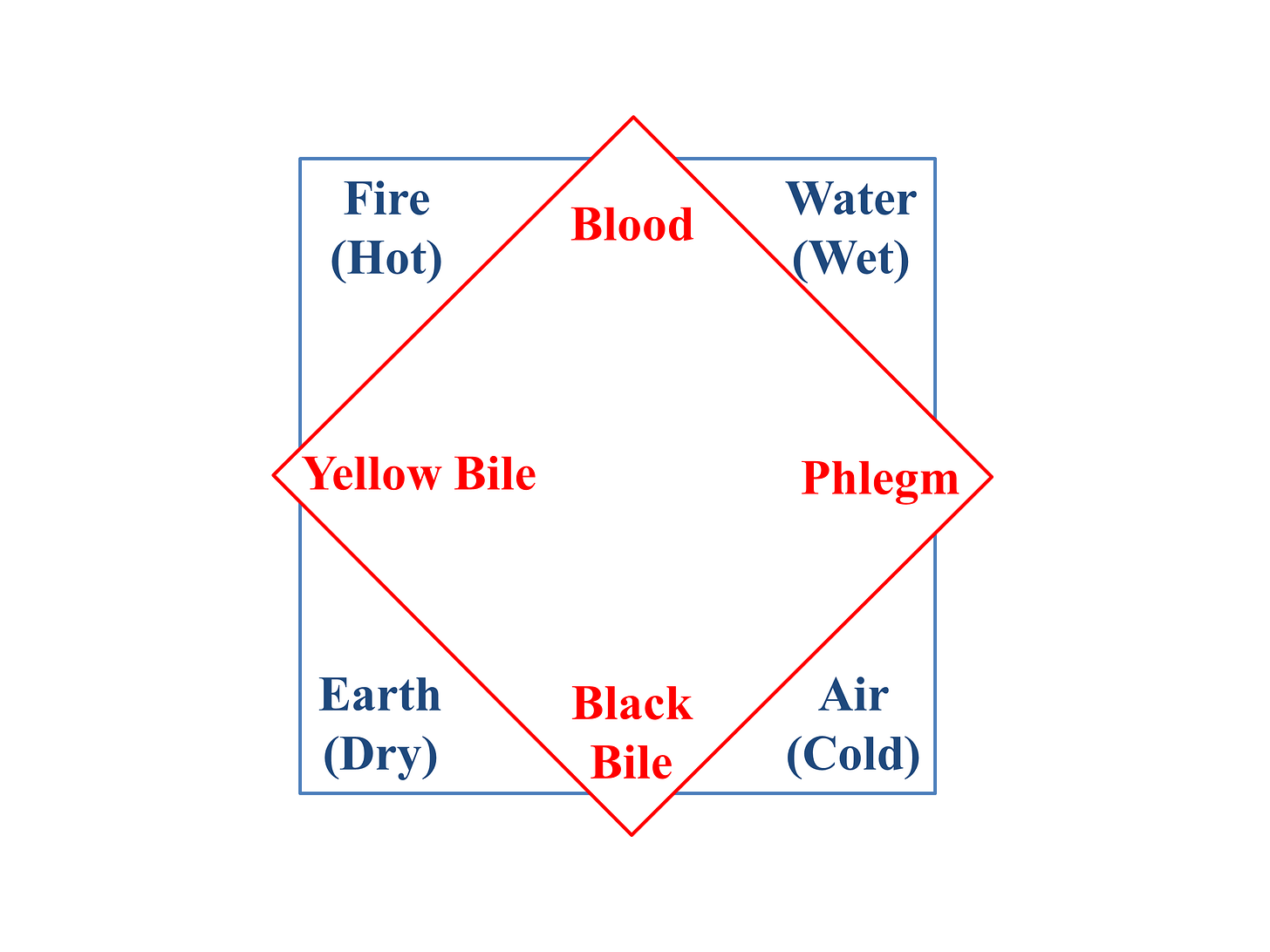

In addition to establishing a medical theory, in which disease is based in natural causation, rather than superstition or magical or spiritual causes, the basis of allopathic medicine was also formed. In Hippocratic medicine, disease was considered to be the result of an imbalance of the bodily humors. These humors were black bile, blood, yellow bile, and phlegm, and each had discrete qualities that could also be positioned across the axes of hot-cold and wet-dry. They were also related to four elements: earth, air, fire, and water.

The Hippocratics also made crucial links between the diet and health, and restrictions in the foods one ate were especially important. Interestingly, although the quote “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food” is often attributed to Hippocrates, it cannot be found directly in the Hippocratic Collection of texts. However, the statement aptly describes the underlying theme of these teachings, many of which include plants that are consumed as both food and medicine.

The Hippocratic texts identify 44 plants as useful in medicinal applications, and describe 22 of these—garlic, celery, leek, flax, beet, cabbage, oregano, elder, sage, barley, rue, fig, fennel, wheat, lentil, pennyroyal, tigernut, blackberry, millet, sesame, onion and coriander—as useful dietary treatments. This article by Touwaide and Appetiti elaborates on ingredients noted in the Hippocratic texts.

Indeed, foods played an important role in allopathy, with “cold” foods being used to treat “hot” disease and “dry” foods being used to treat “wet” disease. The terms “cold” or “hot” do not refer to the temperature or spiciness of the food, but rather are based on other attributions assigned within this system.

Ayurvedic Medicine

Around the same period that the Hippocratics authored the Corpus, one of the most important foundational treatise on Ayruvedic medicine was being recorded in Sanskrit in the Charaka Samhita (Compendium of Charaka). It is one of two major Hindu texts to have survived on the topic of medicine, the other being the Sushruta Samhita, which was dedicated to Ayurvedic medicine and surgery. The Charaka Samhita includes 120 chapters written in poetic style, which describe ancient Ayruvedic theories on human physiology and therapeutics, including sections on the importance of diet and hygiene on health. The pharmaceutical content in the text includes descriptions of how to identify, classify, and prepare medicines from various plants and specific plant parts, as well as from animal and mineral products. The use of animals and their byproducts in medicine is known as zootherapy, and this practice continues today in many forms of traditional medicine.

The proper use of drugs—whether of plant, animal or mineral origin—was also emphasized in these early writings, as evidenced by this translated excerpt from Charaka Samhita:

“Even if the most dangerous poison is used in proper way will become a medicine. Similarly, the drugs if used in improper manner will turn out to be poison. So, if a person who wants health and life should avoid receiving medicines from such physician who is ignorant about the proper use of drugs.”

While many more medical treatises existed in written form in the past, they were most likely lost due to decay or damage over the passage of time. Fortunately, many of the early classical Greek, Latin and Arabic records, upon much of which current allopathic (Western) medicine is based, persist today as many were copied or integrated into newer medical texts over time.

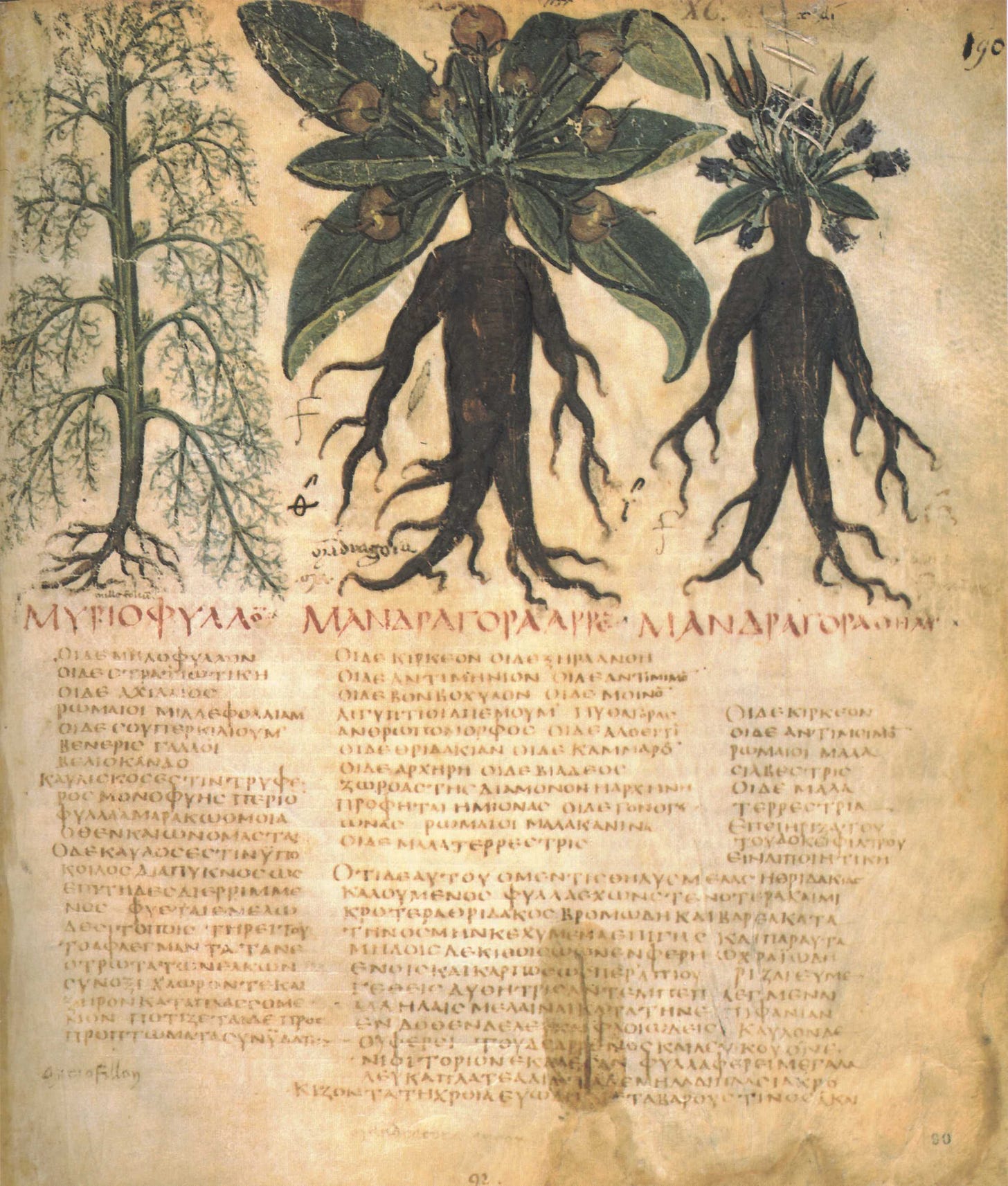

Medicine in the time of the Roman Empire

An excellent example of medical remedies from the time of Nero in the Roman Empire the work of the physician scholar Dioscorides from Anarzbos (1st Century CE). His greatest work was a five-volume book, De Materia Medica (On Medical Material), which served as the precursor for all subsequent pharmacopoeias. Indeed, later premier medical texts, such as Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine, were built upon the groundwork established by his predecessors: Hippocrates (and the Hippocratics), Dioscorides and Galen. For this reason, Dioscorides is widely considered to be the Father of Pharmacology, or the science of drugs, including their origin, composition, therapeutic use and toxicology. Dioscorides documented medicinal uses of approximately 700 plant species, as well as remedies based on ingredients from animal byproducts and minerals; in total he described approximately 1,000 medical formulae. In addition to detailed descriptions of materia medica, this work is particularly rich in color illustrations of plant ingredients. The original text was written in his native language of Greek, but there are a number of copies created centuries later that were translated into several languages, including Latin, Arabic, and Spanish.

Not long after De Materia Medica was compiled, the Roman naturalist, Pliny known as the Elder, completed the comprehensive encyclopedic work Naturalis Historia (Natural History) in 79 CE. Written in Latin, these 37 books covered topics ranging from astronomy and mathematics to botany and anthropology, among others. Most relevant to medical botany are volumes on the topics of botany, medicine and pharmacology.

Galenus, also known as Galen, was a Greek physician in the Roman Empire (129-216 CE). Galen built upon theory of humorism, which was first introduced during the Hippocratic period, by linking four human temperaments to the humoral scheme illustrated above: bilious (choleric, ill-tempered), melancholic (melancholic, thoughtful), phlegmatic (calm, composed, sluggish, apathetic) and sanguine (ruddy, cheerful, optimistic).

The Takeaway

Our present day knowledge of medicine and pharmacology is based upon thousands of years of accumulated wisdom. Over time, ideas were formed, tested by (and on) people, and then either discarded or passed on to the next generation. This process has repeated itself over and over within different cultures and in different languages for as long as humans have existed. We continue this tradition today. Medicine is constantly evolving, as is our relationship with nature. Through looking at the past, we can better appreciate not only how far we’ve come, but also how much more knowledge awaits us in the future.

Yours in health, Dr. Quave

Cassandra L. Quave, Ph.D. is a scientist, author, speaker, podcast host, wife, mother, explorer, and professor at Emory University School of Medicine. She teaches college courses and leads a group of research scientists studying medicinal plants to find new life-saving drugs from nature. She hosts the Foodie Pharmacology podcast and writes the Nature’s Pharmacy newsletter to share the science behind natural medicines. To support her effort, consider a paid or founding subscription, with founding members receiving an autographed 1st edition hardcover copy of her book, The Plant Hunter.

Fascinating review and tour of the Egyptian monuments and hieroglyphics. Decoding these is so fun, and the little dots that signify quantities are so cool.

Fast forward to 1747 when James Lind is credited with the first placebo controlled trial involving sailors, vitamin C, and scurvy. A real quantum leap from our best guesses and intentions to evidence based medicine began.