Herbaria In Peril

How the loss of scientific collections harms research in support of planetary and human health.

I had planned a fun newsletter issue today on the heart health benefits of cacao, in a nod to the tradition of sharing chocolate on Valentine's Day. However, I, along with other members of the scientific community, was blindsided yesterday by the news that Duke University had decided to close the Duke Herbarium!

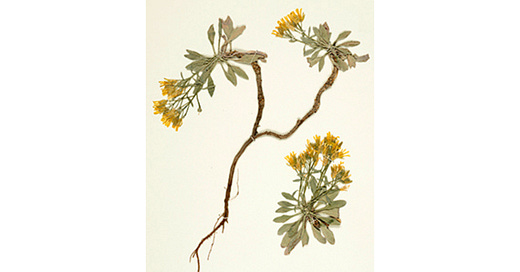

An herbarium is a collection of preserved plant specimens that have been dried and mounted onto acid-free paper, accompanied by data on the date and place of collection, ecosystem characteristics, and the scientific name of the plant. An herbarium serves as a natural history museum on which scientists depend for research on climate change, environmental pollution, biodiversity, evolution, ecosystem dynamics, and even the discovery of new foods and drugs!

Why should I care? I’m not faculty at Duke, nor an I an alum. The reason I care (and you should too) is that Duke University’s herbarium is the second largest private university collection (behind Harvard) in the US, housing over 825,000 specimens. These specimens are especially important as records of plant life throughout the southeastern USA. The famous ferns named after Lady Gaga are also housed there. Among the vascular plants in their collection, they also house an impressive 821 type specimens! Type specimens are the most treasured of all, as they are the physical evidence upon which a species is named. If we can't identify and name plants, it becomes impossible to track when plants become imperiled in the wild or when they go extinct.

This is not the only collection under threat. Countless smaller collections have disappeared over time; some were saved by being absorbed into larger collections, but without funds to support their housing and curation, we are digging an ever-deeper trench from which botany may never emerge. What happens when there are no longer any large collections capable of absorbing these closures? Furthermore, consolidating specimens into a few sites puts them at risk of natural disasters, fires, and more—raising the possibility of losing millions of priceless, centuries-old specimens.

Alarmingly, panicked scientists at the world’s premier botanical research institution, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, which houses over 7 million specimens collected over the past 170 years, have been pleading for help from the public to protest an administrative decision to move the herbarium to a remote site far from the living collections of the garden in London. Out of sight and out of mind? Here is a link to the petition against this move, which elaborates their concerns.

Science Follows the Money

I’m not privy to the inner discussions and debate that led to this decision at Duke. However, based on the December 2023 article in Duke Magazine “Nowhere to Grow” and my own experience as Curator of the Emory University Herbarium over the past 12 years, I can hazard a pretty good guess that it has everything to do with space and money.

As a natural history museum and working collection, herbaria require space to expand as scientists collecting specimens in the field make deposits. This expansion is essential for supporting environmental and botanical field research. In my research, when I am in a remote location learning about the traditional medical uses of a wild plant from a local tribe, the only way to ensure and document the correct identity of the species is by collecting the plant in its fruiting or flowering stage, pressing and drying it, and then depositing it in a herbarium. Without this evidence, it becomes impossible not only to document species in the wild but also to undertake drug discovery research.

Just like a library, herbaria require space and staffing to support the overall academic and scientific research infrastructure of a university. Like a library, these operations do not directly generate income; rather, they support scholarship at large, which can lead to grant income.

Space costs money. Hiring staff or covering faculty salaries to curate and manage herbaria costs money. The challenge is that, unlike other more glamorous and new areas of science, there are almost no grants available to support herbarium operations. If I read one more article about how AI will save the planet, I may scream! AI is only as good as the data it is fed. Without boots on the ground—scientists capable of collecting, identifying, and curating specimens—we've already lost the battle to save our planet's biodiversity.

The perspective of government funding agencies is that operations fall under the university's responsibility. From the university's viewpoint, utilizing space without generating overhead income (indirect dollars that supplement government grants and contribute to the university's operational budget) is seen as a net loss, and therefore of low value to the institution. Consequently, we find ourselves in a quagmire.

Losing Our Way as a Scientific Community

I believe we began to lose our way the moment the university research enterprise transformed into a business model. Today, the value of science is no longer attributed to its contribution to humanity and the generation of knowledge, but rather is measured in terms of the number of grants and the overhead dollars they generate. For comparison, a 5-year research grant from the National Institutes of Health might bring in $1.25 million USD ($250k per year) to directly support a research project (covering salaries, supplies, equipment), and the university receives an overhead on top of that, which can be 56% or more of the base cost ($700k). Universities have come to rely on these funds to operate the costly research enterprise and cover infrastructure costs. In botany, there are few opportunities to bring in such dollars, thus devaluing the field from an operations perspective.

Is This a Harbinger for Things to Come?

I am worried, seriously worried, about our ability as a scientific community to conserve biodiversity and make discoveries that support the health of our planet and human health, especially when the very foundation of such research is being destroyed.

When I became the Curator at the Emory Herbarium in 2012, there was no operational budget to support anything, and emergency financial support from the university has been sporadic at best. I have never taken any salary for the countless hours I dedicate to preserving this collection, conserving every penny we can to cover the salary of one staff person and our supplies.

Over the past 12 years, I have had to beg, borrow, threaten to leave, and hustle to keep operations afloat. We even sold t-shirts to raise money! I've tried to raise awareness about the importance of the herbarium, featuring it in profiles of my work in major media outlets such as The New York Times Magazine, National Geographic Magazine, National Geographic Channel, NPR, ABC News, PBS, and more. I've accepted many speaking engagements and spent time away from my family not for personal financial gain, but to direct honorarium dollars into supporting the herbarium operations.

Our doors remain open today only because of the support from some incredible philanthropists, and our community and student volunteers. It has been a frustrating and heartbreaking journey, to say the least. Knowing that I'm not alone, that other scientists are fighting to save their herbaria, doesn't make the situation any better. Instead, it makes my experience feel even more tragic.

How Can You Help?

While I don’t have the answers on how to save the Duke Herbarium, I do have them for the Emory Herbarium. This year, the Emory Herbarium celebrates its Diamond Jubilee, marking 75 years of research and education on plants. In celebration of this milestone, we are hosting a number of events across Atlanta and beyond. First up are our events with the Atlanta Science Festival, which you can read more about here: March 12th at the Carter Center and March 23rd at Piedmont Park.

A major goal this year is to secure a $2M endowment for the herbarium. Endowments generate an average income of 5%, meaning a $2M endowment would generate a $100k annual operating budget indefinitely. This would ensure that the Emory Herbarium will be preserved not only during my tenure at Emory but well beyond my retirement and death.

What You Can Do:

Share this post! Please help to get the word out.

If you are a current student, employee, or alum of Duke, reach out to their leadership to let them know how important their herbarium is and that it is worth saving!

Help me to save the Emory Herbarium! We are in need of funds to support our current operational budget and our endowment campaign.

We are urgently seeking larger donations to the Emory Herbarium endowment campaign. Donations can come in the form of cash, stock, estate planning, and more. Moreover, donations can be divided up over 5 years for annual installments. Please contact Phillip Brooks from Emory Advancement at philip.brooks@emory.edu or (678) 801-5909 for more details on how to give to the endowment campaign. Every bit helps!

The Takeaway

The situation with the Duke collection has underscored a clear lesson: no matter how valuable these collections are to science, they remain at risk without steady financial support. Thank you, as always, for your support of research and education in the science of planetary and human health 💚

I’ve opened up comments to all readers on this one. I look forward to your thoughts.

Yours in health, Dr. Quave

Cassandra L. Quave, Ph.D. is a scientist, author, speaker, podcast host, wife, mother, explorer, and professor at Emory University School of Medicine. She teaches college courses and leads a group of research scientists studying medicinal plants to find new life-saving drugs from nature. She hosts the Foodie Pharmacology podcast and writes the Nature’s Pharmacy newsletter to share the science behind natural medicines. To support her effort, consider a paid or founding subscription, with founding members receiving an autographed 1st edition hardcover copy of her book, The Plant Hunter.

Available in hardcover, paperback, audio, and e-book formats!

In light of Duke's announcement that it will close its herbarium, Cassandra Quave points out very clearly the importance of herbaria for scientific research. She runs the one at Emory. Everyone interested in biology and science should worry about this.

Had to incorporate many university herbaria into NMW when I ran that; now 15 years later researchers at one university have realised they need one for teaching… too late, too late