Pomegranate Power: How Fruit Waste Could Fight Superbugs

New research from the Quave (Emory Univ.) and Zara (Univ. Sassari) labs uncovers punicalagin, a polyphenol from pomegranate peels, as a potent natural antimicrobial against staph bacteria.

When we think of pomegranates, it’s usually the tasty jewel-like seeds that come to mind—not the peels we toss aside. But in a new collaborative study between researchers in my lab at Emory University (Atlanta, GA) and collaborating researchers at the University of Sassari (Sardinia, Italy), we turned our attention to these neglected peels and made a surprising discovery. We found that punicalagin, a compound abundant in pomegranate rinds, is a key driver behind the plant’s antimicrobial effects—especially against Staphylococcus aureus, a common and sometimes drug-resistant bacterial pathogen. This work not only sheds light on the healing power locked within food industry byproducts, but could also lead to innovative solutions for food safety and public health.

The full scientific paper is available to all via open access, just published in the American Chemical Society Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, available online here:

Salim A, Marquez L, Jakkala K, Woo S, Caputo M, Fancello F, Deiana P, Santona M, Molinu MG, Quave CL, Zara S. Identification of Punicalagin as a Key Bioactive Compound Responsible for the Antimicrobial Properties of Punica granatum L. Peel Extract against Staphylococcus aureus. J Agric Food Chem. 2025 Jul 9. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5c02320. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40629888.

Study Overview

Our study focused on bioassay-guided fractionation of pomegranate peel extract (PPE) to pinpoint the compound responsible for its antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus. Among the many phytochemicals found in pomegranate, punicalagin—a type of ellagitannin—emerged as the lead compound driving these effects. We used two pomegranate cultivars grown in Sardinia, selected for their robust antibacterial properties. We used high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and mass spectrometry to isolate and identify the α and β anomers of punicalagin as the active constituents.

Study Methods

Pomegranate peels were dried, ground, and extracted using 80% ethanol. Extracts from seven different cultivars were screened for antimicrobial activity. Two of the most promising cultivars, including the Selezione Siciliana Primosole, were selected for further fractionation and analysis. Antibacterial activity was evaluated using MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) assays against multiple strains of S. aureus, while cytotoxicity was assessed in human keratinocyte (HaCaT) cells. Finally, we applied the most active extracts to real food systems (cheese and ground meat) to test their antibacterial effects in real-world conditions.

Major Findings

Punicalagin as an Antimicrobial Agent

Out of 87 samples tested, fractions containing punicalagin consistently demonstrated the strongest antibacterial activity. Pure punicalagin (α and β forms) inhibited S. aureus growth at concentrations as low as 16 μg/mL. Importantly, this activity occurred without causing cytotoxic effects in human skin cells, highlighting punicalagin’s promise for safe use in food or topical applications. The antimicrobial action was not due to interference with quorum sensing—a bacterial communication system—but appeared to stem from direct effects on bacterial survival.

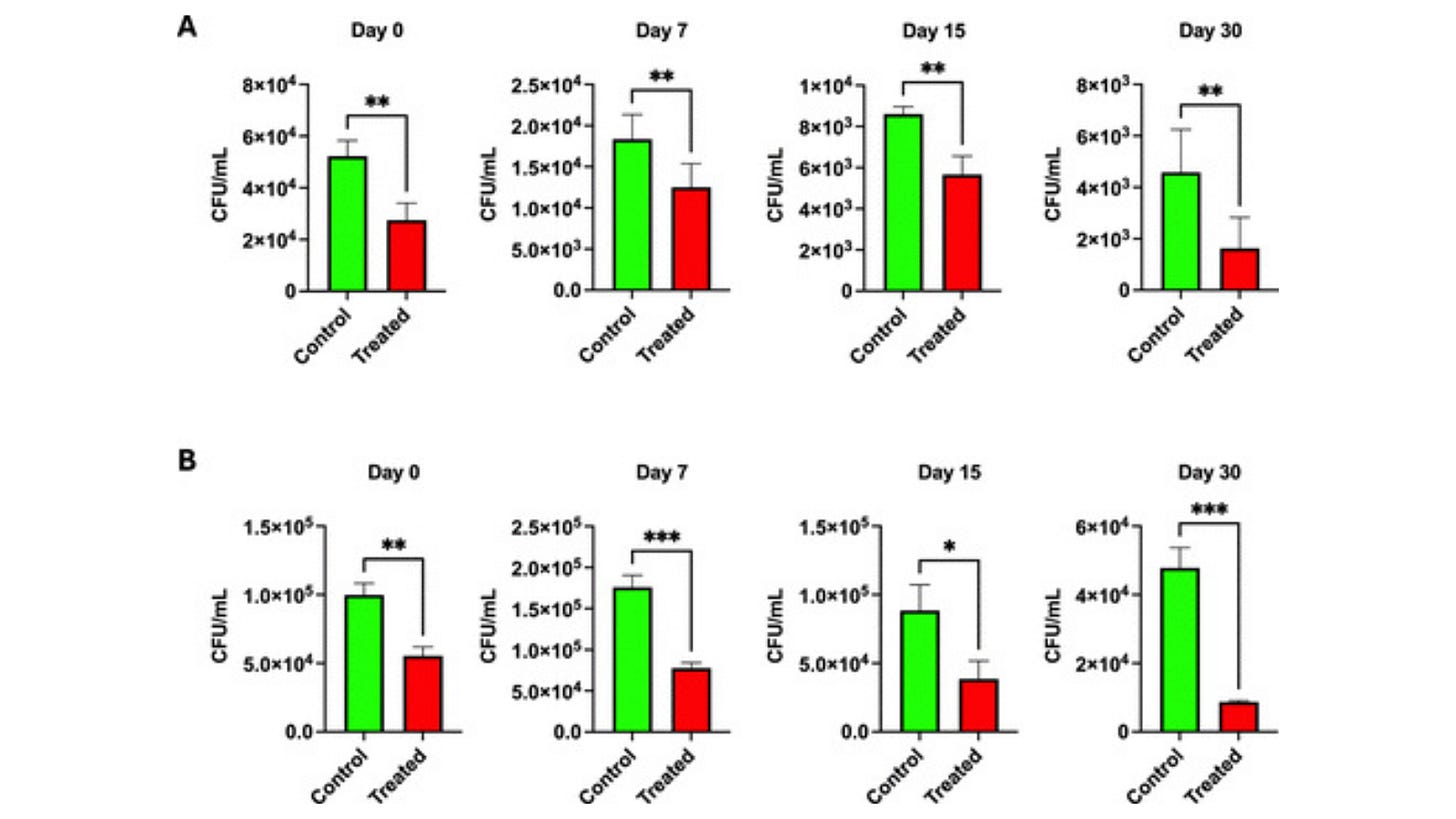

Real-World Food Applications

To test practical applications, we introduced the pomegranate peel extract (PPE) into cheese and ground meat models contaminated with S. aureus. Treated foods showed a significant reduction in bacterial counts compared to untreated controls—up to a 0.8-fold decrease in viable cells. The PPE also delayed spoilage, reducing mold growth in cheese and preserving color in meat samples. These findings position PPE as a viable natural preservative that may extend shelf life while combating pathogens.

Safe for Human Cells, Tough on Bacteria

Cytotoxicity testing revealed that punicalagin-rich fractions were not harmful to human keratinocytes even at concentrations up to 128 μg/mL. This selectivity supports the potential for punicalagin to be used in topical formulations to prevent or treat skin infections, including those caused by antibiotic-resistant strains of S. aureus.

The Takeaway

This study highlights the untapped potential of pomegranate peel, a food processing byproduct that is often discarded, as a natural source of antimicrobial compounds. By identifying punicalagin as a key antibacterial agent, our work opens new doors for natural food preservation, cosmetic development, and medical applications that target resistant pathogens. With rising concerns over antibiotic resistance and chemical preservatives in our foods, nature may already be offering us a plant-powered solution.

Yours in health, Dr. Quave

Cassandra L. Quave, Ph.D. is a Guggenheim Fellow, CNN Champion for Change, Fellow of the National Academy of Inventors, recipient of The National Academies Award for Excellence in Science Communication, and award-winning author of The Plant Hunter. Her day job is as professor and herbarium director at Emory University School of Medicine, where she leads a group of research scientists studying medicinal plants to find new life-saving drugs from nature. She hosts the Foodie Pharmacology podcast and writes the Nature’s Pharmacy newsletter to share the science behind natural medicines. To support her effort, consider a paid subscription to Nature’s Pharmacy or donation to her lab research.

The Plant Hunter is available in hardcover, paperback, audio, and e-book formats!

Great news! I know natural products can't be patented but is there anyway to protect your discovery from being used by others to make products? That would make a good post topic. :-)