Should you swap out your plastic toothbrush for a stick?

Chewing sticks have been used for oral hygiene for thousands of years, particularly in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. I explore how they work and how they compare to toothbrushes and toothpaste.

For millennia, people have used plants to improve dental health and maintain oral hygiene, and this practice still persists today in many communities around the world.

The modern toothbrush

The origin of the modern toothbrush can be traced back to Babylonians who used chewing sticks as early as 3500 BC. Toothpicks, which were also used to clean teeth and the mouth, were mentioned in ancient Greek and Roman literature. Chewing sticks are made from various plant species and are commonly used for dental hygiene in Asia, Africa, South America, and the Middle East.

Environmental considerations of modern toothbrushes

Manual toothbrushes are made from nylon and polypropylene plastic—both of which are sourced from nonrenewable fossil fuels. The American Dental Association (ADA) recommends that you replace your toothbrush every three to four months. Every year, Americans throw away an estimated 1 billion toothbrushes, adding 50 million pounds of waste to landfills. This plastic waste also finds its way into waterways and oceans, hurting marine life.

How a toothbrush works

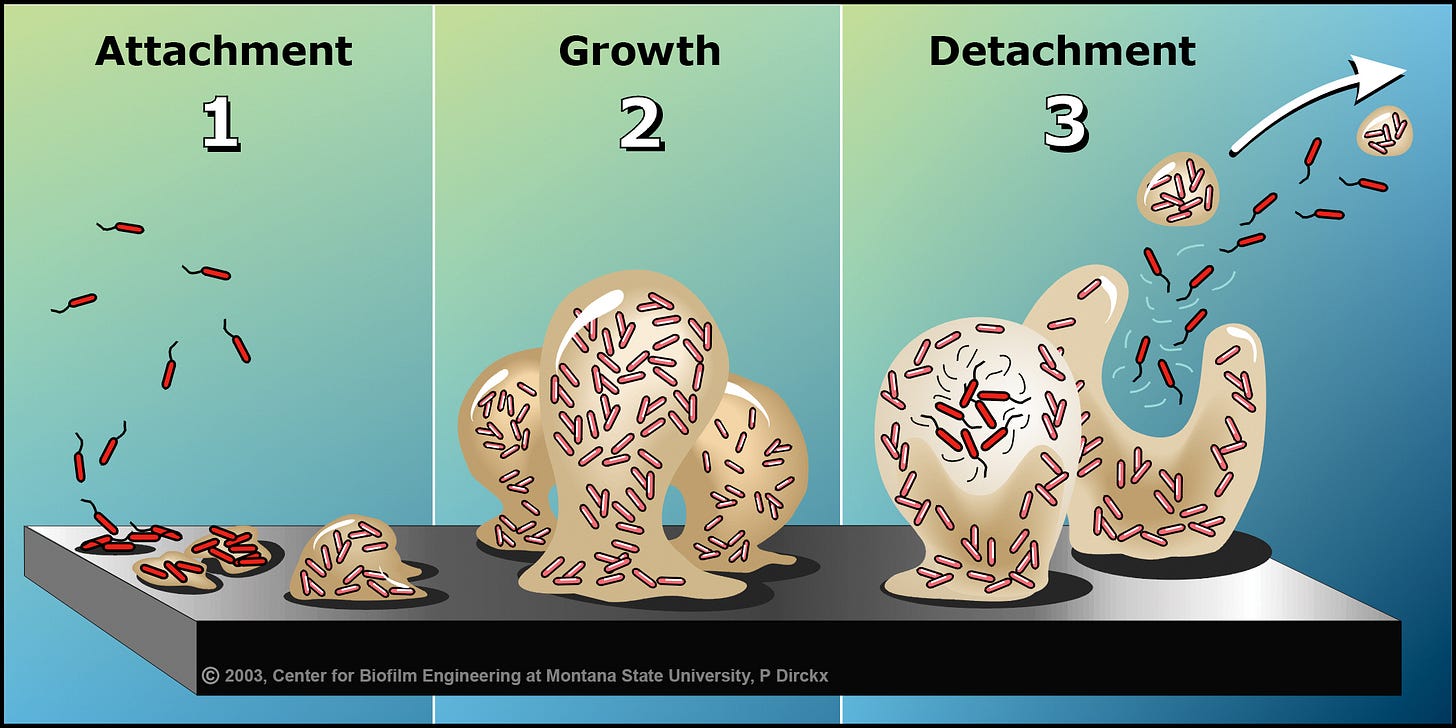

Your teeth are coated by microbes that form a community known as a biofilm. Microbes are at their weakest when they exist as free-floating individuals in the body. As a community, however, microbes can better coordinate actions and build up defensive structures, such as the slimy biofilm matrix, to better protect themselves. On the teeth, this biofilm is known as plaque. You can feel the biofilm on your teeth by rubbing your tongue across the tooth surface in the morning. That slimy, gritty texture you feel is the microbial biofilm formed overnight while you slept!

If left unchecked, the biofilm (plaque) can harden and develop into tartar, which must be scraped off. Regular removal of this biofilm from the teeth is necessary to support health of your teeth and gums. Gingivitis (inflamed gums) and periodontitis (inflammation leading to shrinkage of the gums and loosening of the teeth) can develop in the absence of regular oral hygiene.

The ADA recommends:

Brushing twice per day for 2 minutes each time

Using a toothpaste which contains fluoride (fluoride helps to harden enamel and protect teeth from cavities)

Using a toothbrush with soft bristles

Cleaning between the teeth

These recommendations highlight the importance of both the mechanical removal of biofilm (through brushing/flossing and use of abrasive silica in the toothpaste) and chemical strengthening (fluoride on enamel) of teeth.

The chewing stick

A chewing stick is a thin wooden stick that is used for cleaning teeth and freshening breath. It is typically made from the stem of a plant and can be cut from a variety of trees or shrubs. The stick is chewed on one end to create frayed bristles, which are then used to brush teeth. The stick needs to be fresh and pliant with a gentle bend to it. In other words, if the stick is dry and snaps with pressure, it is no longer useful.

Can any shrub or tree be used as a chewing stick?

No! While nature offers many benefits, not all plants are safe for human use. Some trees and shrubs contain harmful or toxic plant chemicals. However, over time, certain plant species have been identified in different parts of the world as safe and effective for cleaning teeth. Neem and miswak are among the most widely used plants for this purpose. Here, I focus on miswak, which comes from the Salvadora persica plant in the Salvadoraceae family. The term "miswak" is derived from Arabic and means "tooth-cleaning stick."

Chewing stick vs. modern toothbrush: What do they share in common?

Mechanical disruption of the biofilm:

The frayed bristles of the chewing stick are effective in physically disrupting biofilm (plaque) on the teeth.

One of the chemical constituents in miswak is silica—the same abrasive chemical used in many brands of toothpaste.

Chemical protection of the teeth:

One of the chemical constituents in miswak is fluoride—the same chemical added to many brands of toothpaste to strengthen tooth enamel.

Along with its utility in mechanically disrupting biofilm and strengthening enamel, several studies have reported that miswak exhibits antimicrobial properties against microbes of importance to oral health, including the bacteria Streptococcus mutans and the yeast Candida albicans.

Findings from clinical trials

Many studies have been conducted to examine the utility of miswak in different patient populations. Here are the major findings from a few of these studies:

One randomized controlled clinical trial in children with a high risk of dental caries (cavities) compared tooth brushing with miswak chewing sticks versus with fluorinated tooth paste on manual toothbrushes. They found that both practices significantly reduced plaque scores in the children. Of note: they also found that children using miswak experienced a change in their salivary microbiome composition towards bacterial species with less risk of inducing caries.

One clinical study on healthy male volunteers found that miswak use resulted in a significant reduction in the bacteria Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, a part of the subgingival plaque microflora found in association with periodontitis.

A 2022 meta-analysis found that miswak offers similar outcomes to toothbrushing when considering reduction in the mean plaque scores. The study authors also noted a reduction in the mean gingivitis scores when miswak was used in addition to toothbrushing.

What to expect

I recently taught my lecture on oral health and hygiene in the Botanical Medicine and Health course at Emory University. A big believer in experiential learning, I offered students the opportunity to try miswak for themselves. As I don’t have access to a Salvadora persica tree in Atlanta, I ordered pre-packaged miswak online.

The sticks came in individually wrapped plastic packaging. Upon opening the packaging, we noted a distinctive woodsy smell of the sticks. We also gently bent the the sticks and noted that they were pliant. Here’s how we prepared the chewing sticks for use:

We each used a knife to gently peel off around 3/4” of the bark on one end the stick.

We chewed that part of the stick between our molars for about 1 minute. The taste takes some getting used to! Also note that miswak stimulates salivation and many of us felt the urge to spit out excess saliva during this part of the preparation.

Once the distinct bristles were formed, we held the chewing stick like a pencil and gently rubbed our teeth with the bristles.

To help you follow each step easily, I recommend checking out this helpful Wiki-How guide which provides visual illustrations. Remember that you can soften the bristles by soaking them in water before your next use. And when the bristles become brittle or frail, simply clip off the used end of the stick and repeat the process to make a new brush from the same stick.

When do I use miswak?

While I don't use miswak every day, I find it particularly useful to bring along on camping trips and during travel. Beyond the clinical evidence of its utility in oral hygiene, three major advantages are that:

It doesn’t require water to use it.

It doesn’t require toothpaste—the critical ingredients found in toothpaste like fluoride and silica are already in the stick!

It can be trimmed and reused until it gets too short to reach my back teeth.

Do you use chewing sticks for oral hygiene and health? I’d love to hear from you! Comment below on what your experience has been like and if you prefer miswak or another species for this purpose.

Yours in health, Dr. Quave

Nature’s Pharmacy is written by Cassandra L. Quave, Ph.D.—a disabled writer, speaker, podcast host, professor, wife, mother, explorer, and ethnobotanist. Dr. Quave is Associate Professor of Dermatology and Human Health at Emory University School of Medicine. She has written about her work as a scientist in The Plant Hunter: A Scientist’s Quest for Nature’s Next Medicines (Viking/Penguin 2021). During the day, she teaches college courses and leads a large group of talented research scientists studying medicinal plants in the search for new life-saving drugs from nature. In her spare time she hosts the Foodie Pharmacology podcast and writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to share the incredible science behind the medicines found in nature. This newsletter is only possible through the generous support of fellow Nature’s Pharmacy community members. To support this effort and join the community, please consider a paid or founding subscription. Founding subscribers will receive an autographed 1st edition hardcover copy of The Plant Hunter!

Super interesting! Taking miswak camping....that seems a good idea:)