Cancer cures and blueprints from nature

Reflections on the drug discovery path from plant to pharmaceutical.

Yesterday, I gave a lecture to my undergraduate Botanical Medicine and Health course on some important cancer therapies derived from molecules first identified in plants. Nature is the best chemist, but it does have its limitations—sufficient yields of the active molecule or high toxicity, for starters. As I walked through one example after another of how different cancer drugs were derivatized—created through modification of the original blueprint discovered in nature—I thought perhaps you all might like to learn about this as well! So, here we go. Today I’ll share the story of the Chinese Happy Tree and a starting compound that was too toxic for human use.

Blueprints from nature

What do I mean by ‘blueprints’ from nature? I’m talking about the chemical structures of molecules produced by plants. There are thousands of different molecules found in even a single leaf! Plants produce these to serve a number of purposes. In some cases, it is for defense against other organisms that might harm the plant (insects, hungry mammals, or microbes) or to attract organisms to aid plants in pollination or spreading their seeds. When it comes to medicine, sometimes we can find molecules in plants that can be used as a drug or used as a starting point for developing a new drug.

Cancer drugs from plants

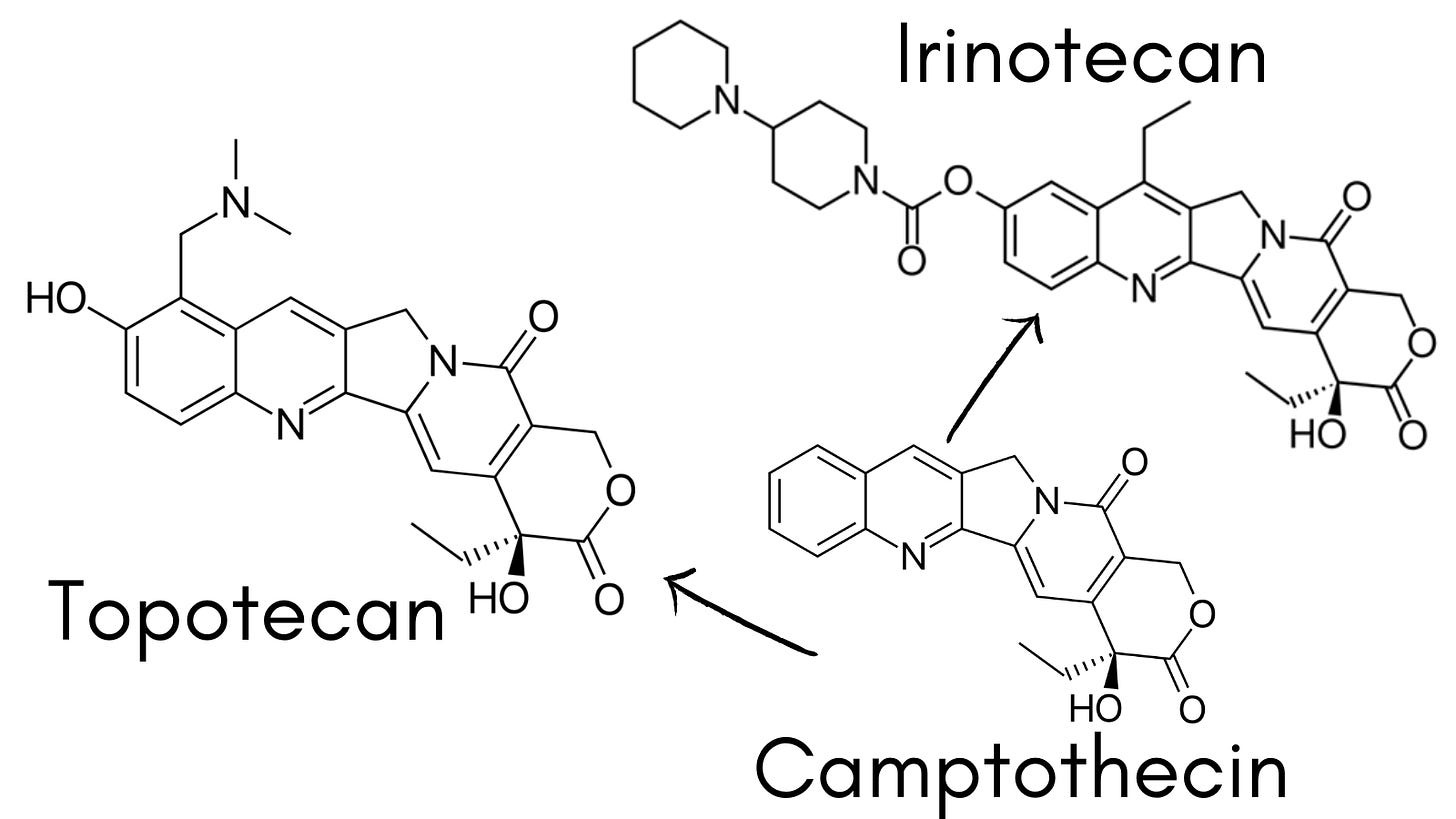

There are several great discovery stories of cancer drugs from plants. We have the Chinese happy tree (scientific name: Camptotheca acuminata) to thank for camptothecin and its subsequent products inspired by the original plant molecule (Irinotecan and Topotecan). There are examples from other plants such as the Madagascar Periwinkle (source of the vinca alkaloids) and the Mayapple, which inspired etoposide and teniposide. Another important cancer drug is Taxol, discovered in the Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia). In case you missed it before, here is an earlier post that explains the historic and cultural significance of yew trees, especially the English yew (Taxus baccata). Today, I’ll focus on the story of camptothecin and its derivatives.

Lessons from the Yew Tree

In the heart of the tiny village of Fortingall, Scotland, stands an ancient yew tree—the Fortingall Yew—enveloped by the serene ambiance of a small churchyard cemetery. This tree, possibly the oldest in Europe, is a living testament to history, its roots entwined with centuries of Celtic lore. The scientific name of this yew tree is

From plant to drug

In the 1960s, the US National Cancer Institute funded research by scientists Drs. M.E. Wall and M.C. Wani. They discovered an alkaloid, camptothecin, from the stem and bark of the Chinese Happy Tree (Camptotheca acuminata). This tree is native to China and is used in Traditional Chinese Medicine. This was an exciting discovery! Camptothecin works by inhibiting Topoisomerase I, which prevents DNA from unwinding. It showed activity against leukemia in lab tests, but the problem was that it was far too toxic for human use.

What to do? This is a common story in the discovery of new medicines from nature. Sometimes, a great molecule shows a lot of promise in treating a challenging disease but may lack certain qualities that make it unsuitable for use as a drug in its current state. For example, it might have poor solubility or distribution to the sites where it's needed in the body. Or, as in the case of camptothecin, it may be too toxic to be tolerated as a drug.

The good news is that we have chemical tools that scientists can use to build off of the starting blueprint of the original plant-derived molecule. Indeed, this is exactly what was attempted in the case of camptothecin, yielding many new semi-synthetic products inspired by camptothecin’s chemical blueprint, two of which made it through FDA approval and into the clinic: Irinotecan and Topotecan.

What was better about these new versions of the molecule? The structural changes were effective in reducing drug toxicity and improving activity against certain types of cancer. Topotecan (sold under the brand name Hycamtin) is now used to treat lung, ovarian, and other forms of cancer. In 2007, the FDA approved it for oral use, making it the first among topoisomerase I inhibitors to be available as a pill.

Irinotecan (sold under the brand name Camptosar) is used today to treat colon and small cell lung cancers. It is often used in combination with another drug for the best outcomes and is delivered by IV.

The Takeaway

What can we learn from the case of the Chinese Happy Tree? First, I think it presents a clear example of how plants can provide us with an incredible starting point for drug design. This story also makes me wonder about how many other discoveries await. There are so many important medicinal plants that have never been subjected to rigorous scientific examination, and we have much to learn from nature.

Yours in health, Dr. Quave

Cassandra L. Quave, Ph.D. is a scientist, author, speaker, podcast host, wife, mother, explorer, and professor at Emory University School of Medicine. She teaches college courses and leads a group of research scientists studying medicinal plants to find new life-saving drugs from nature. She hosts the Foodie Pharmacology podcast and writes the Nature’s Pharmacy newsletter to share the science behind natural medicines. To support her effort, consider a paid or founding subscription, with founding members receiving an autographed 1st edition hardcover copy of her book, The Plant Hunter.

Available in hardcover, paperback, audio, and e-book formats!

I find this endlessly fascinating! Thank you for this and the work you do.

Fascinating, and so interesting that a lot of these compounds were teased out over thousands of years in Chinese medicine. Do you see any role for AI in winnowing down candidate molecules at this time?